Chapter 5 - Quantum Information: Basic Principles and Simple Examples

Contents

Introduction

Quantum computers may be a few years away. However, some quantum information processing tasks that can be performed presently are quite interesting and informative. In this chapter we will examine a few of these. In addition, we add related material that provides constraints on our ability to manipulate quantum information. Until fairly recently, these constraints have been considered a problem (or just the way things are) and were not considered further. Now these attitudes have changed and these constraints have been found to be useful. These two constraints, the uncertainty principle and the no-cloning theorem, are presented here because they are very important to the effectiveness of the BB84 protocol as well as other quantum key distribution (QKD) protocols.

No Cloning!

Quantum mechanics is quite different from classical mechanics and some of these differences are more striking than others. One particularly striking example is the so-called ''No Cloning Theorem'' primarily attributed to Wootters and Zurek [8]. (See also the review of the no-cloning theorem [15] and References therein.)

The general statement of the theorem is as follows.

No Cloning Theorem:

No quantum operation exists that can duplicate perfectly an arbitrary quantum state.

To put it another way, there is no universal quantum copying machine that will take in a state and put out two copies of the same state for any given input state. There is a very simple way to see that this is true, even if there are deeper reasons behind it. Following Neilsen and Chuang [2], let us consider an easy way to see this and postpone a more thorough discussion for now. In this theorem, the difference between quantum information and classical information is striking, since one may take any piece of paper and put it on a copier and get two that are nearly identical. Alternatively, you could take a picture.

Suppose there was a quantum copying machine. This machine would take some arbitrary input state (also possibly some ancillary quantum system ), and produce two copies of that state. Let us use as our unitary (remember, this is how states transform) that performs the copying. (One can think of as the action performed by a copying machine, like a photocopier, and as the blank paper on which the copy will be written.) Then

| (5.1) |

This, of course, must be true for any state. It then follows that it must also be true for , meaning

| (5.2) |

Now we can multiply the right-hand side of Eq.(5.1) with the Hermitian conjugate of the right-hand side of Eq.(5.2) and similarly with the left-hand sides of these two equations. This gives

| (5.3) |

Assuming is normalized, this gives

(If it is unclear how this result was obtained, see Section C.7.)

The only way that a number would be equal to its square is if it is zero or one. This means that the two states are either the same or orthogonal. This obviously excludes arbitrary states---which is what we wanted to begin with. It is therefore not possible to have a cloning (or copying) machine for quantum states.

Uncertainty Principle

The uncertainty principle is something that is considered very important to all of quantum theory. There is no close classical analog. It is introduced here for lack of a better place to put it. However, it will be used later quite often and is central to many quantum phenomena.

Consider two observables and . The variance of these can be written as

| (5.4) |

for . The uncertainty principle is

| (5.5) |

Quantum Dense Coding

Quantum dense coding is an interesting communication protocol to begin our discussion of quantum information processing. It shows how information is obtained from a quantum state and it uses entangled states to do this. It is also a very simple protocol.

The idea is to send two bits of information from one person to another. The sender is commonly referred to as Alice and the receiver Bob. Bob will get two bits of information, but Alice will only send one qubit. Two bits can only be in one of four possible states: or .

We begin with the following Bell state,

| (5.6) |

Suppose Alice has the first of these two qubits and Bob the second. We might then write the state in the following way to be even more explicit:

| (5.7) |

Then Alice will decide whether to act with , or on her qubit. She will then send that qubit to Bob, who will act on the two qubits and measure. He will then have two bits of information from Alice who will have only sent one qubit to him. So for one qubit sent (and some shared entanglement), two bits of information can be transferred.

Let us examine the specific protocol. Alice decides which she wants to send, or , i.e. the two bits of information to Bob. She then acts on with , or respectively, giving the following for each action:

| (5.8) |

Now, Alice sends her qubit to Bob. Having both qubits, Bob now acts with a CNOT on the two qubits to obtain the following:

| (5.9) |

(Recall a CNOT acts on two qubits and flips the second one if the first is in the one state and does nothing if it is in the zero state.)

Now Bob acts with a Hadamard gate on the first qubit (the one Alice sent). Recall the Hadamard gate, , acts in the following way: , , and . Then

| (5.10) |

Therefore, if Alice has sent , then Bob will be able to recover and find and similarly for the other three possibilities. Thus it was possible for Bob to extract two bits of information from Alice's single transmitted qubit after a little bit of manipulation.

Teleporting a Quantum State

Teleportation is an interesting protocol for several reasons. First and foremost, for our considerations is that it is a simple protocol which is easily described using what we already know.

Here is the scenario. Suppose Alice wants to send Bob a state and let us further suppose that Alice doesn't know the state. We can write the state in the form

| (5.11) |

Now if Alice wants to specify the state exactly to Bob using classical information, it would be impossible. This is because Alice would need to know the numbers and exactly and they may be irrational numbers of arbitrary precision. (You may say that we never need to know anything to arbitrary precision, but that somewhat misses the point. It's not, in principle, possible to do it classically. There is no way for Alice to send Bob an arbitrary number of digits in a finite time. This is if she knows the state. We are saying that she does not need to know it. Also, she can't know find out what the state is through measurment since a measurement in the basis will return one or the other with some probability. It will not give her the coefficients.) However, she can teleport the state exactly using the following protocol.

Alice wants to send the state to Bob and suppose that they share a state between them

| (5.12) |

where, as before, the first qubit is in Alice's possession and the second qubit is in Bob's possession. So we could write it as

| (5.13) |

However, it will be understood that the first particle is Alice's and the second Bob's.

Now, Alice also has , so together we can write the total system's state as

| (5.14) |

Now Alice can act on the two qubits in her possession with a CNOT gate. This produces:

| (5.15) |

Now she applies a Hadamard gate to the first qubit to get

| (5.16) |

where the second equality follows from rearranging terms. Now Alice measures the first two qubits which are in her possession. If she gets the result she tells Bob that he has the state. If she gets the result , then she tells Bob to apply an operation to the state in his possession and then he'll have . If she gets , she tells him to apply a operation, and if she gets she tells him to apply . In each case, he will obtain the desired state thus ''teleporting'' the state from Alice to Bob.

QKD: BB84

The objective of cryptography is to encode information in such a way that only the sender and receiver can read the information transmitted between them. Many ingenious codes have been developed, but none are complete secure with the exception of the one-time key pad. This is a randomly generated key that allows the sender to encode information, the receiver to decode the information, and allows no others to decifer it since it is randomly generated and used only once.

Quantum cryptography provides a way in which to generate a shared random key. The amazing thing is that, in the ideal case, it can be proven secure even though it is transmitted over a public channel. Since this method of cryptography works by the generation of a key, it is often called quantum key distribution (QKD). The simplest protocol for generating such a key is called the BB84 protocol after Bennett and Brassard, its inventors. (See Gisin, et al. and references therein for a nice history of quantum cryptography.)

Quantum cryptography is now an active field (again, see Gisin, et al.) with systems being developed for commercial use. (Some such systems already exist.) However, most (if not all) protocols which enable secret communication using quantum states are based on the very simple ideas contained in the BB84 protocol. It is therefore instructive, as well as quite interesting from a quantum information prespective, to introduce this protocol here and show how it works.

Polarization

This section may be skipped by people who know the basics of polarized light and the detection of polarization of light.

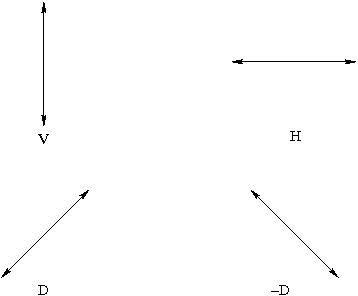

Alice and Bob will create a one-time key to encode a secret message to be shared by them. They will do this by creating and measuring the polarization of photons. These photons will have one of four possible polarizations H, V, D, or -D and denoted in Figure 5.1

Suppose a photon is prepared in the polarization state H. Then suppose that the photon is then impinges upon a polarizer that is set to transmit photons of polarization H. This photon may be observed on the other side of the polarizer with a photodetector. However, if the polarizer is set in the V direction, meaning it will transmit a photon polarized in the V direction, then the H-polarized photon will not be transmitted.

Now the point that will be important for QKD is the following. Suppose Alice prepares the photon in the state H, denoted and Bob measures in the -D/D basis. In that case, Bob has a probability of 1/2 of having the photon transmitted and a probability of 1/2 that he will detect no photon, i.e., the photon was not transmitted. This would be written as . In this case there is no way to predict which he will obtain, a photon or no photon.

Similarly if Alice prepares the photon in the state D, denoted and Bob measures in the H/V basis, Bob has a probability of 1/2 of having the photon transmitted and a probability of 1/2 that he will detect no photon. In this case, and again there is no way to predict with certainty which he will obtain, a photon or no photon.

|

Figure 5.1: Four different choices for the choice of polarization of photons used in the QKD protocol.

Alice and Bob Create a Key

Alice will send single photons to Bob. She will randomly choose one of four possible different polarization directions for the photon to be sent, H, V, D, -D. For each photon, Bob will randomly choose a measurement basis H/V or -D/D and measure the polarization of the photons sent by Alice. (Examples are given in Figure 5.1.) After a sequence of photons has been sent, Alice and Bob will compare the bases they used for preparation and measurement of the photons using a public channel through which to communicate. If their bases agree, then they will record the result of the measurement. (Examples are given in Table 5.1.) Bob knows what he measured and Alice knows what she sent. However, they will not discuss the result publicly, only the basis. If the bases the two have chosen do not agree, they discard the result of the measurement. In this way, they will generate a random key for a message that they will later exchange, each knowing the key. Of course, they send enough photons in order to encode the message which will later be sent in binary.

| Alice Sends | Bob Measures | Result |

| H | V | 0 |

| D | H | discard |

| D | -D | 0 |

| V | V | 1 |

| -D | H | discard |

| H | D | discard |

| V | -D | discard |

| V | H | 1 |

Notice they will agree about half of the time on the basis, so they

will need to send many more qubits than they will later use for their

key. Also, as discussed next, they will discard some of those for

which their bases agree in order to detect any eavesdropper.

Eve the Eavesdropper

At this point, Alice and Bob share a key. But how do they know it is a secret key that only the two of them share? What if some eavesdropper (appropriately named Eve) tries to intercept their key in transit? If this can be done, Eve can later decode the message Alice and Bob want to keep secret.

Let us suppose that Eve measures every photon intended for Bob. If she does, she has a probability of 1/2 of choosing the correct basis for each measurement. If she measures the photon's polarization she will either find that she has either detected a photon or not with her polarization measurement. (It is, of course, the same as Bob's. She sends the photon through a polarizer, if it is transmitted, she records the result and if it is not, she records the fact that it has not.) Now if she measures in the same basis as Alice used for the preparation, then she records the result and sends the same type of photon to Bob. This will happen with probability 1/2. However, if she uses the wrong basis for her measurement, which will happen with probability 1/2, she will obtain a result, and based on that result, send a photon to Bob. Now if she does not measure in the same basis that Alice used for the preparation (which happens, on average, half of the time), she will get a result which is determined by the wrong basis; then send on that result to Bob which is prepared by Eve in the wrong basis (different from Alice's). When Bob gets the photon that Eve has sent, he will measure it in the basis which does not agree with Alice's. (Note that if Alice and Bob's basis measurement does not agree then they discard anyway. So that is not a case that needs to be considered.) On average, half of the time he will get the result which Alice sent (by chance) and so neither Bob nor Alice will be able to detect this. However, if he gets a different answer, the eavesdropping can be detected. This error will occur with probability 1/4 (= 1/2 probability Eve's measurement is different from Alices times 1/2 probability Bob's result differs from what Alice sent). Thus if Alice and Bob publicly discuss their results for, say 1/4, of their results and the error rate is significantly below 1/4, then they can be sure that Eve has not been intercepting their key and sending things to Bob to mask her interference. Examples are given in Table 5.2.

| Alice Sends | Eve Measures | Eve Sends | Bob Measures |

| H | V | H | H |

| D | H | H | -D |

| D | -D | D | D |

| V | D | H | H |

| V | H | V | V |

| -D | H | V | -D |

| H | D | -D | V |

| V | D | H | H |

![{\displaystyle \sigma _{1}^{2}\sigma _{2}^{2}\geq \left({\frac {1}{2i}}\langle [{\mathcal {O}}_{1},{\mathcal {O}}_{2}]\rangle \right)^{2}.\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a11a939869af78bb975bb0d5d20a546d9bbf7d47)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}H_{1}CNOT_{12}&={\frac {1}{2}}\alpha _{0}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\otimes (\left\vert 00\right\rangle +\left\vert 11\right\rangle )+{\frac {1}{2}}\alpha _{1}(\left\vert 0\right\rangle -\left\vert 1\right\rangle )\otimes (\left\vert 10\right\rangle +\left\vert 01\right\rangle )\\&={\frac {1}{2}}[\left\vert 00\right\rangle (\alpha _{0}\left\vert 0\right\rangle +\alpha _{1}\left\vert 1\right\rangle )+\left\vert 01\right\rangle (\alpha _{0}\left\vert 1\right\rangle +\alpha _{1}\left\vert 0\right\rangle )\\&\;\;\;\;+\left\vert 10\right\rangle (\alpha _{0}\left\vert 0\right\rangle -\alpha _{1}\left\vert 1\right\rangle )+\left\vert 11\right\rangle (\alpha _{0}\left\vert 1\right\rangle -\alpha _{1}\left\vert 0\right\rangle )],\end{aligned}}\,\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cbdac9cbf369e9257d83c5de0cfe3b084095761e)